24. Complex Numbers Solutions Part 4#

Clearly A is (1, 0) or (-1, 0). Let A is (1, 0). Then \(z = cos0 + isin0.\) Clearly, B and C would be \(cos120 + isin120\) and \(cos240 + isin240.\)

Equation of line \(DM\) can be found from straight line formula. Line \(AM\) is perpendicular to \(BD\) and \(BD = 2AC\) so \(A\) can be found.

Vector representing line joining \(z_1\) and \(z_2\) is \(z_2 - z_1.\) Now if this is rotated by 90 degree and shifted by \(z_2 - z_1\) then it would represent side joining \(z_2\) and \(z_3.\) First let us rotate it so line segment is \((z_2 - z_1)(cos90 + isin90)\) i.e. \(i(z_2 - z_1).\) Now shifting this by \(z_2 - z_1\) we get \(z_3 - z_1 = iz_2 - iz_1 + z_2 - z_1\) i.e. \(z_3 = -iz_1 + (1 + i)z_2.\) Similarly \(z_4\) can also be found.

Clearly, \(z_2 = z_1(cos(120 + arg(z_1)) + isin(120 + arg(z_1)))\) Similarly, \(z_3 = z_1(cos(240 + arg(z_1) + isin(240 + arg(z_1)))\) which can be computed.

We know that three vertices represent an equilateral triangle if \(z_1^2 + z_2^2 + z_3^2 - z_1z_2 - z_2z_3 -z_1z_3 = 0.\) Substituting the respective values we get

\[a^2 - 1 + 2ai + 1 - b^2 + 2bi - a + b - abi - i = 0 \]Equating real and imaginary parts we get

\[a^ - b^2 - a + b = 0 \Rightarrow (a - b)(a + b + 1) = 0 \]So either \(a = b\) or \(a + b = -1\) but if we choose \(a + b = -1\) then the other part leads us to \(ab = 3\) which is not solvable.

Choosing \(a = b\) the imaginary part becomes

\[2a + 2b - ab - 1 = 0 4a - a^2 - 1 = 0 a = 2 \pm \sqrt{3}\]But \(a = 2 + \sqrt{3}\) does not make triangle equilateral. So \(a = b = 2 - \sqrt{3}.\)

156 and 157 are left as exercises to the reader.

Three points \(z_1, z_2\) and \(z_3\) will be collinear if

\[\begin{vmatrix} z_1 & \overline{z_1}&1\\ z_2 & \overline{z_2}&1\\ z_3 & \overline{z_3}&1 \end{vmatrix}=0 \]Given our three points they become collinear when substituted in this equation.

If \(P\) divides \(6i\) and \(3\) internally, then P is

\[z = \frac{6i + 6}{2 + 1} = 2 + 2i \]If \(P\) divides \(6i\) and \(3\) externally, then P is

\[z = \frac{6i - 6}{2 - 1} = -6 + 6i \]The mid-point is \(4-2i\). Thus, locus of \(P\) is a circle at center represented by complex number \(4 -2i\) whose radius is \(\sqrt{4^2 + 2^2}\) i.e. \(\sqrt{20}\).

Clearly, \(z\) satisfies \(z\overline{z} = (4+2i)2 + (4-2i)\overline{z}.\)

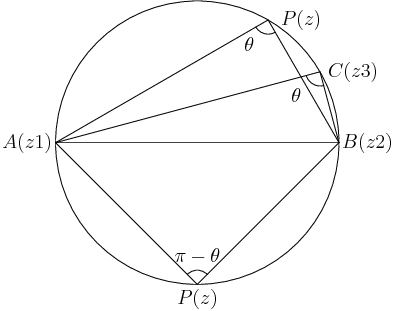

Let three non-collinear points be \(A(z1), B(z2)\) and \(C(z3)\). Let \(P(x)\) be any point on the circle. Consider the following diagram:

Then either \(\angle ACB = \angle APB\) (when they are in the same segment) or \(\angle ACB + \angle APB = \pi\) (when they are in the opposite segment).

\[arg\left(\frac{z_3 - z_2}{z_3 - z_1}\right) - arg\left(\frac{z - z_2}{z - z_1}\right) = 0 \]or

\[arg\left(\frac{z_3 - z_2}{z_3 - z_1}\right) + arg\left(\frac{z - z_1}{z - z_2}\right) = \pi \]\[arg\left[\left(\frac{z_3 - z_2}{z_3 - z_1}\right)\left(\frac{z - z_1}{z - z_2}\right)\right] = 0 \]or

\[arg\left[\left(\frac{z_3 - z_2}{z_3 - z_1}\right)\left(\frac{z - z_1}{z - z_2}\right)\right] = \pi \]In any case, we get \(\frac{(z_3 - z_2)}{(z_3 - z_1)}\frac{(z - z_1)}{(z - z_2)}\) is purely real. Hence, proved.

Following from previous problem we have one equation for the condition for the four vertices to be cyclic. Also, sum of all four angles of the quadrilateral is equal to be \(2\pi\). From these two equations, the results can be deduced.

We have to prove that

\[\begin{split}\begin{vmatrix}z_1 & z_1' & 1\\z_2 & z_2' & 1\\z_3 & z_3' & 1\end{vmatrix} = 0\end{split} \]i.e.

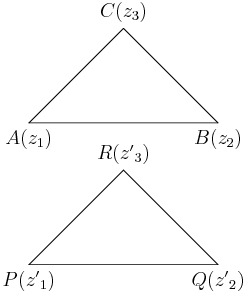

\[z_1({z^\prime}_2-{z^\prime}_3) + z_2({z^\prime}_3-{z^\prime}_1)+z_3({z^\prime}_1-{z^\prime}_2) = 0 \]Consider following two triangles:

\(\triangle ABC\) and \(\triangle PQR\) will be similar if all their angles are equal and ratios of sides as well.

\(\angle BAC = \angle QPR\) i.e.

(1)#\[arg\left(\frac{z_3 - z_1}{z_2 - z_1}\right) = arg\left(\frac{{z^\prime}_3 - {z^\prime}_1}{{z^\prime}_2 - {z^\prime}_1}\right)\]\(\frac{AB}{PQ} = \frac{AC}{PR}\) or \(\frac{AC}{AB} = \frac{PR}{PQ}\)

or

(2)#\[\frac{z_3 - z_1}{z_2 - z_1} = \frac{{z^\prime}_3 - {z^\prime}_1}{{z^\prime}_2 - {z^\prime}_1}\]

From (1) and (2), upon simplification we get the desired result.

From these two equation we have

\[r = \frac{c - a}{b - a} \]and

\[r = \frac{\omega - u}{v -u} \]Equating these two equations and taking modulus and argument, it follows from the previous problem that the two triangles are similar.

Let point \(z\) lies on the perpendicular bisector then we know that all the points on perpendicular bisector will be equidistant from \(z_1\) and \(z_2\). Thus, the equation is \(|z - z_1| = |z - z_2|\).

Mid-point of such a diameter is \(\frac{z_1 + z_2}{2}\). Let \(P\) be a point lying on this circle, which, is represented by complex number \(z\). Thus, the equation of circle is \(\left|z - \frac{z_1 + z_2}{2}\right| = \left|z_1 - \frac{z_1 + z_2}{2}\right|\) or \(\left|z - \frac{z_1 + z_2}{2}\right| = \left|z_2 - \frac{z_1 + z_2}{2}\right|\).

The equation can be written as \(\left|z - z_1\right| = c\left|z - z_2\right|\), which, when substituted with \(z_1 = x_1 + iy_1\) and \(z_2 = x_2 + iy_2\) gives following

\[\left|(x - x_1) + i(y - y_1)\right| = c\left|(x - x_2) + i(y - y_2)\right| \]\[(x - x_1)^2 + (y - y_1)^2 = c^2\{(x - x_2)^2 + (y - y_2)^2\} \]which, upon simplification gives equation of a circle.

Given equation is \(\left|z\right| = 1\) i.e. \(\left|z\right|^2 = 1\) i.e. \(z\overline{z} = 1\) i.e. \(2z\overline{z} = 2\) i.e.

\[\frac{2}{z} = 2\overline{z}. \]\(L.H.S. = \left|z_1 + z_2\right|\) \(\Rightarrow \left|z_1 + z_2\right|^2 = {r^2}_1 + {r^2}_2 + 2r_1r_2cos(\theta_1 - \theta_2).\) Similarly, \(\left(\left|z_1\right| + \left|z_1\right|\right)^2 = \left({r^2}_1 + {r^2}_2 + 2r_1r_2\right).\)

Thus, \(cos(\theta_1 - \theta_2) = 0\) \(\Rightarrow arg(z_1) - arg(z_2) = 2n\pi.\)

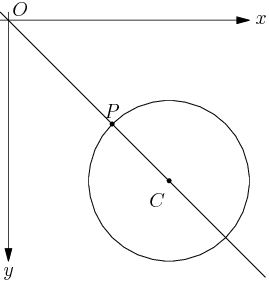

The equation \(\left|z - 2 + 2i\right| = 1\) represents a circle with center at \((2, -2i)\) with unity radius. Since, the line between \((2, -2i)\) and origin will make an angle of \(45^\circ.\) This is shown in the following diagram:

Therefore, \(P\) is \(2 - \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} + i(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} -2)\)

This is similar problem to previous one and has been left as an exercise to the reader.

From given equation,

\[\left(\frac{\left|z-1\right| + 4}{3\left|z - 1\right| + 2}\right) = \frac{1}{2} \]\(\Rightarrow \left|z - 1\right| > 10\)

This represents area which lies outside a circle with center at \((1, 0)\) and radius 100.

Let \(z = x + iy\) then the equation becomes \(x^2 - y^2 + x + 1 + iy(1 + 2x) = 0\). Clearly, imaginary part has to be zero i.e. either \(y = 0\) or \(x = -\frac{1}{2}\). So, it is real and positive for all points on the x-axis. When, \(x = -\frac{1}{2}\) the real part becomes \(y^2 = \frac{3}{4}\). Thus, for points \(x = -\frac{1}{2}\) and \(-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}<y<\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\) the required condition is satisfied.

First equation represents a circle whose center is at \((0, ia)\) and radius equal to \(\sqrt{a + 4}\). The second equation represents interior of a circle with center at \((2, 0)\) and radius unity. Now, for the possibility of existence of \(z\) the two circles must intersect each other.

\(C_1C_2 < r_1 + r_2\) i.e. \(\sqrt{a^2 + 4} < 1 + \sqrt{a + 4}.\)

Solving this equation will yield the range of \(a\) for which condition is satisfied.

This is similar problem to previous one and has been left as an exercise to the reader.

This is similar to 170 and has been left as an exercise to the reader.

This is similar to previous one and has been left as an exercise to the reader.

This is similar to 173 and 174 and has been left as an exercise to the reader.

\(Re(1 + i)z^2 = x^2 - y^2 -2xy > 0\) which is true for \(y = 0\) and values of \(y\) within \(-1 \pm \sqrt{2}x.\)

This is an easy problem and has been left as an exercise to the reader.

This is an easy problem and has been left as an exercise to the reader.

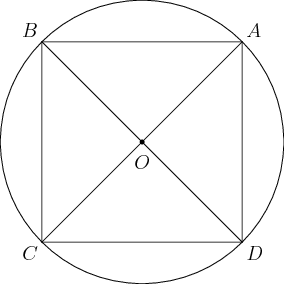

Consider the following picture:

Given, \(b_1z_1 + b_3z_3 = -(b_2z_2 + b_4z_4)\) and \(b_1 + b3 = -(b_2 + b_4)\)

\[\therefore \frac{b_1z_1 + b_3z_3}{b_1 + b_3} = \frac{b_2z_2 + b_4z_4}{b_2 + b_4} \]The point dividing \(AC\) in the ratio \(b_3:b_1\) is same as the point dividing \(BD\) in the ratio \(b_4:b_2\). Let this point be \(O\).

Let, \(b_1b_2\left|z_1 - z_2\right|^2 = b_3b_4\left|z_3 - z_4\right|^2\)

\[\Rightarrow b_1b_2AB^2 = b_3b_4CD^2 \]\[b_1b_2(b_3^2 + b_4^2 -2b_3b_4cos\alpha) = b_3b_34(b_2^2 + b_1^2 - 2b_1b_2cos\alpha) \]\[\Rightarrow \frac{b_3}{b_4} + \frac{b_4}{b_3} = \frac{b_1}{b_2} + \frac{b_2}{b_1} \Rightarrow \frac{b_3}{b_4} = \frac{b_1}{b_2} \]\[\Rightarrow \frac{AO}{OC} = \frac{BO}{OD} \]i.e. \(\triangle AOB\) is similar to \(\triangle COB\). Similarly, \(\triangle AOD\) is similar to \(\triangle BOC\) i.e. \(\angle DAO = \angle OBC\) i.e. points \(A, B, C\) and \(D\) are concyclic.

Let \(f(x) = k(x - \alpha)(x - \beta - i\gamma)(x - \beta + i\gamma)\) i.e. \(f(x) = k(x - \alpha)[(x - \beta)]^2 + \gamma^2]\)

\(f^\prime(x) = k[{(x - \beta)^2 + \gamma^2} + (x - \alpha)2(x - \beta)]\) i.e. \(k[3x^2 -2(a + 2\beta)x + \beta^2 + \gamma^2 + 2\alpha\beta]\)

Descriminant of above equation is given by

\(D = 4[(\alpha + 2\beta)^2 -3(\beta^2 + \gamma^2 + 2\alpha\beta)]\) i.e. \(4(\alpha^2 + \beta^2 -3\gamma^2 -2\alpha\beta)\)

The roots are complex if \(D < 0\) i.e. \((\beta - \alpha)^2 < 3\gamma^2\) i.e. \(\left|\beta - \alpha\right| < \sqrt{3}\left|\gamma\right|\).

This is possible if \(A\) lies inside the equilateral triangle with base \(BC\).

Let \(a = \alpha + i\beta\) and \(z = x + iy\), then \(\overline{a}z + a\overline{z} = 0\) becomes as \(\alpha x + \beta y = 0\) or \(y = \left(\frac{-\alpha}{\beta}\right)x.\)

Its reflection in the x-axis is

\[y = \frac{\alpha}{\beta}x or \alpha x - \beta y = 0 \]\[\left(\frac{a + \overline{a}}{2}\right)\left(\frac{z + \overline{z}}{2}\right) - \left(\frac{a - \overline{a}}{2}\right)\left(\frac{z - \overline{z}}{2}\right) = 0 \]\[\Rightarrow az + \overline{a}\overline{z} = 0 \]- \[z = \frac{\alpha + \beta t}{\gamma + \delta t} \Rightarrow (\gamma + \delta t)z = \alpha + \beta t \Rightarrow (\delta z - \beta)t = \alpha - \gamma z \]\[\Rightarrow t = \frac{\alpha - \gamma z}{\delta z - \beta} \]

As \(t\) is real,

\[\frac{\alpha - \gamma z}{\delta z - \beta} = \frac{\overline{\alpha} - \overline{\gamma z}}{\overline{\delta z} - \overline{\beta}} \]\[\Rightarrow (\alpha - \gamma z)(\overline{\delta z} - \overline{\beta}) = (\overline{\alpha} - \overline{\gamma z})(\delta z - \beta) \](3)#\[\Rightarrow (\overline{\gamma}\delta - \gamma\overline{\delta})z\overline{z} + (\gamma\overline{\beta}-\overline{\alpha}\delta)z + (\alpha\overline{\delta} - \beta\overline{\gamma})\overline{z} = (\alpha\overline{\beta} - \overline{\alpha}\beta)\]Since \(\frac{\gamma}{\delta}\) is real, \(\frac{\gamma}{\delta} = \frac{\overline{\gamma}}{\overline{\delta}}\) or \(\gamma\overline{\delta} - \delta\overline{\gamma} = 0\)

Therefore, (3) can be written as

\[\overline{a}z + a\overline{z} = c\]where \(a = i(\alpha\overline{\delta}) - \beta\overline{\gamma}\) and \(c = i(\overline{\alpha}\beta - \alpha\overline{\beta})\)

Note that \(a \ne 0\) for if \(a = 0\) then

\[\alpha\overline{\delta} - \beta\overline{\gamma} = 0 \]\[\Rightarrow \frac{\alpha}{\beta} = \frac{\overline{\gamma}}{\overline{\delta}} = \frac{\gamma}{\delta} \]\[\Rightarrow \alpha\delta - \beta\gamma = 0. \]which is against the hypothesis.

Also, note that \(c = i(\overline{\alpha}\beta - \alpha\overline{\beta})\) is a purely real number. Thus, \(z = \frac{\alpha + \beta t}{\gamma + \delta t}\) represents a straight line.

\((3 + 3\omega + 5\omega^2)^2 - (2 + 6\omega + 2\omega^2)\) i.e. \((3 + 3\omega + 3\omega^2 + 2\omega^2)^2 - (2 + 2\omega + 2\omega^2 + 4\omega)\) i.e. \(4\omega^4 - 4\omega = 0 \because \omega^3 = 1\)

- \[(2 - \omega)(2 - \omega^2)(2 - \omega^{10})(2 - \omega^{11}) \]\[= (2 - \omega)(2 - \omega^2)(2 - \omega)(2 - \omega^2) \]\[= [(2 - \omega)(2 - \omega^2)(2 - \omega)(2 - \omega^2)]^2 \]\[= (4 - 2\omega - 2\omega^2 + \omega^3)^2 \]\[= (5 - 2(\omega + \omega^2))^2 \]\[= (5 + 2)^2 = 49 \]

Evaluating,

\[[(1 - \omega)(1 - \omega^2)]^2 \]\[= [1 -(\omega + \omega^2) + \omega^3]^2 \]\[= [1 - (-1) + 1]^2 = 9 \]Evaluating,

\[(-\omega -\omega)^5 + (-\omega^2 - \omega^2)^5 \]\[= -32\omega^2 - 32\omega = 32 \]5th and 6th parts are left as exercises for the reader.

- \[a^2 + b^2 + c^2 - ab - bc - ca = a^2 + \omega^3b^2 + \omega^3c^2 + (\omega + \omega^2)ab + (\omega + \omega^2)bc + (\omega + \omega^2)ca = (a^2 + ab\omega + ca\omega^2) + (ab\omega^2 + b^2\omega^3 + bc\omega) + (ca\omega + bc\omega^2 + c^2\omega^3) = a(a + b\omega + c\omega^2) + b\omega^2(a + b\omega + c\omega^2) + c\omega(a + b\omega + c\omega^2) = (a + b\omega + c\omega^2)(a + b\omega^2 + c\omega)\]

Let \(x = \sqrt{-1 - \sqrt{-1 - \sqrt{-1 - ... to \infty}}}\)

\(\therefore x = \sqrt{-1 - x}\) or \(x^2 = -1 - x\) or \(x^2 + x + 1\). Thus, the two roots are \(\omega\) and \(\omega^2.\)

This problem has been left as an exercise to the reader.

\(a^2 - ab + b^2 = a^2 + (\omega + \omega^2)ab + b^2\omega^3\)

\(\Rightarrow a^2 + ab\omega + ab\omega^2 + b^2\omega^3\)

\(\Rightarrow a(a + b\omega) + b\omega^2(a +b\omega)\)

\((a +b\omega)(a + b\omega^2)\)

It can be solves as 1.

\(a^3 + b^3 = (a + b)(a^ - ab + b^2)\) which can be solved using 2.

\(a^3 - b^3 = (a - b)(a^2 + ab + b^2)\) which can be solved using 2 as well.

Given expression is \((a + b + c)(a^2 + b^2 + c^2 - ab - bc - ca).\) Now this can be solved using previous problems’ solution

\(x^2 + x + 1 = 0 \Rightarrow x = \frac{-1 \pm \sqrt{3}}{2} = \omega or \omega^2\)

When \(x = \omega\), \(x^{3p} + x^{3q+1} + x^{3r+2}\)

\(= \omega^{3p} + \omega^{3q+1} + \omega^{3r+2}\)

\(= 1 + \omega + \omega^2 = 0\)

When \(x = \omega^2\), \(x^{3p} + x^{3q+1} + x^{3r+2}\)

\(= \omega^{6p} + \omega^{6q+2} + \omega^{6r+4}\)

\(= 1 + \omega + \omega^2 = 0\)

Since all the roots of the equation \(x^2 + x + 1\) satisfies the given expression it is divisible by \(x^2 + x + 1.\)

It is similar to 190 and has been left as an exercise to reader.

It is an easy problem and requires simplification and thus has been left as an exercise to the reader.

Similar to 192 it requires simple calculation and has been left as an exercise to the reader.

It is another easy problem and has been left as an exercise to the reader.

Hint: Use Euler’r formula and take i out from denominator to solve it.

Hint: Using quadratic equation formula the roots are:

\[z = \frac{2 cos \theta \pm \sqrt{4 cos^2 \theta - 4}}{2} = cos\theta \pm isin\theta \]Now the expression can be easily evaluated using De’Moivre’s formula.

Given, \(x_r = cos\frac{\pi}{2^rr} + isin\frac{\pi}{2^r} = e^{\frac{i\pi}{2^r}}\)

Thus, \(x_1x_2x_3 ... to \infty\)

\(= e^{i\pi\left(\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{2^2} + \frac{1}{2^3} + ...\right)}\)

Using sum for infinite terms of a G.P.

\(= e^{i\pi}\)

\(= -1\)

\(L. H. S. = \left[\sqrt{2}\left\{cos\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right) + isin\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)\right\}\right]^n + \left[\sqrt{2}\left\{cos\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right) - isin\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)\right\}\right]^n\)

Simplifying this using De’Moivre’s formula we get our desired result.

- \[\sum_{k = 1}^6\left(sin\frac{2\pi k}{7} -icos\frac{2\pi k}{7}\right) \]\[= -i \sum_{k = 1}^6\left(cos\frac{2\pi k}{7} + isin\frac{2\pi k}{7}\right) \]\[= -i \sum_{k = 1}^6 e^{\frac{i2\pi k}{7}} \]\[= -i \left[e^{\frac{i2\pi}{7}} + e^{\frac{i4\pi}{7}} + .. + e^{\frac{i12\pi}{7}}\right] \]\[= -i \left[\left(\frac{1 - e^{2\pi}}{1 - e^{\frac{i2\pi}{7}}}\right) - 1\right] \]\[= -i [0 - 1] = i \]

Let \(cot^{-1}p = \theta\), then \(cot\theta = p\). Now, L. H. S. is

\[e^{2mi\theta}\left(\frac{icot\theta + 1}{icot\theta - 1}\right)^m = e^{2mi\theta}\left[\frac{i(cot\theta - i)}{i(cot\theta + i)}\right]^m \]\[= e^{2moi\theta}\left(\frac{cos\theta - isin\theta}{cos\theta + isin\theta}\right)^m \]\[= e^{2mi\theta}\left(\frac{e^{-i\theta}}{e^i\theta}\right)^m = e^2mi\theta . e^{-2mi\theta} = e^0 = 1 \]